(To view our November/December 2018 issue of ClubWEST online, click here.)

By Mike Williscraft

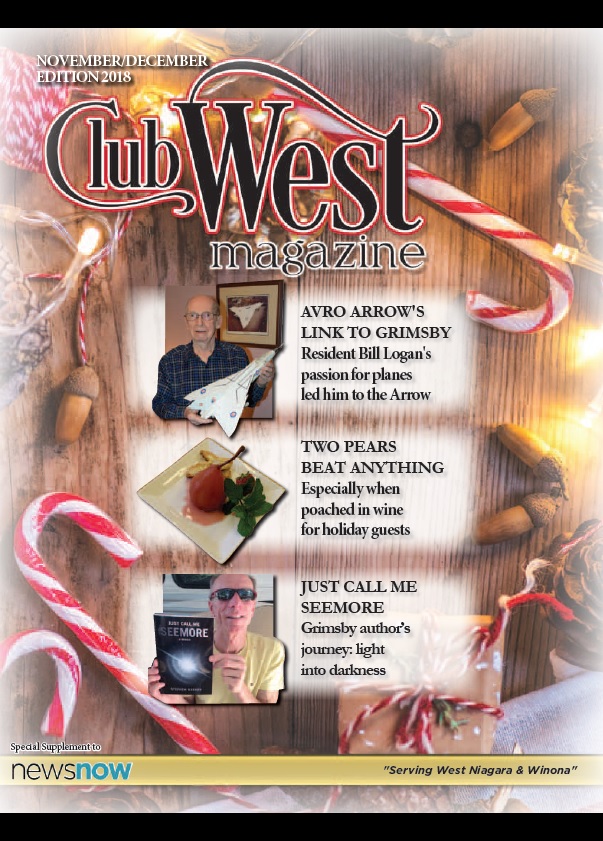

What is one of Canada’s most legendary mysteries is a vivid memory for Grimsby’s Bill Logan.

The Avro Arrow – infamous for its seemingly arbitrary cancellation by then-Prime Minister John Diefenbaker in February 1959 – is still looked at as an engineering marvel.

This although Diefenbaker ordered every plan, every blueprint, every complete Arrow and all materials related to testing destroyed. Simply, he ordered that every aspect of the project be shredded, burned and/or eliminated.

For Bill, now 96 years old, was fulfilling a lifelong interest in planes and aeronautical engineering when he took a job at Avro Canada, based in Malton, Ont., at the end of WWII.

Avro – with its parent company in England – on its own was a mercurial Canadian success story which opened its doors in 1945 and, at its peak, employed more than 50,000 people with 15,000 of those employees working at the Malton plant and fellow subsidiary Orenda Engines.

Previous to the engineering work on the Arrow, Avro had gained a top-drawer reputation with planes such as the Avro Lancaster Bomber as evidence of their efforts and expertise.

With dedicated employees like Bill in their fold, success was almost guaranteed.

Bill, a Niagara Falls native, adored planes from the time he was a toddler.

“It was all I thought about when I was a youngster,” said Bill with a smile, adding, “you can put the P.Eng. after my name because I am still an engineer.”

“I built more than 100 model planes. I was interested in aircrafts right from the start.

With aeronautics as his sole goal, a university degree in engineering was his immediate goal as a youth.

“I checked out Toronto and Montreal but they didn’t have degrees, I wanted the degree as well, so I went to University of Michigan.

Crossing the border for studies or socializing was much more simple in that era.

“Growing up in Niagara Falls it was nothing to hop across the river for a coffee or entertainment,” Bill recalled.

As a side note Bill noted that he is likely the only living person left who would have seen the collapse of the border bridge in Niagara Falls in 1940.

“It collapsed due to ice build up. I was right there,” said Bill.

Bill got two years in at UofM before WWII broke out, at which time he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Much of his time in the RCAF was spent at the airbase in Dunnville.

“Because of my stature, they wanted me to be a gunner on a bomber,” said Bill.

“But I had red/green blindness, so I could not do it.”

Because of his knowledge, it made sense to keep Bill involved with pilots and flying so he began his stint training air crew on how the aircrafts work – all phases.

“I got them trained, then the fellas left here for England to join the war effort,” said Bill.

War time in Niagara was a pretty simple time as resources were scarce, something many today would find hard to believe.

“I had an old Chevy so I could get back and forth to Niagara Falls. You couldn’t get tires, so mine had a lot of patches. If you had a problem, you patched it and kept going,” recalled Bill.

“And that was if you could get gas. It was not unusual for a gas station to have a ‘no gas’ sign up.”

So when he had no gas but had to get some place, he used his thumb.

“Hitchhiking was not a problem back then. If you had a uniform on, somebody would pick you up right away,” he said.

“One time in Niagara Falls, I got picked up by a snow plow in a big storm. He needed help working the wing, so I rode with him all the way to Dunnville working that wing.

With the end of the war, soldiers returned home on a “first in, first out” basis. This meant Bill would be released towards the end of the process. This would have compromised his return to UofM to complete his engineering studies, so he wrote a letter asking for permission for early release so he could get to school in time for the semester start.

“The granted my request, so I was one of the first soldiers to return to civilian life. The other fellas weren’t back for another six months or so,” Bill recalled.

“They gave us $150 and told us we could wear our uniforms for one month after we got out. For some, those were the only clothes they had. I was a bit of a celebrity. I got invited everywhere. It was great. I told them I was Canadian but they said that did not matter.. It was a fun time.”

And part of his fun at UofM was extra-curricular activities. Bill was a champion badminton player for Big Blue.

When his second stint at UofM wrapped up, he had a summer work placement and then it was time to job hunt. Post-war, it was not much of a hunt.

“It was really easy to get a job. You didn’t need any experience. When I was done with school, I went to Avro to apply. I got in right away. My first job was just drawing different designs, like wings. Gradually, you worked your way through different aspects of design and eventually I was moved into electrics and hydraulics,” said Bill.

For Bill, who knew what he wanted to do with his life right from the moment he gave it a first thought was now living his dream.

The first major project he worked on for Avro was the Canuck fighter. He spent about 10 years on that project. In 1957, he started working on the Arrow.

For an aeronautical engineer, working on the Avro Arrow was the Super Bowl of jobs. There was nothing in the world at that time which was more dynamic, more cutting edge and more challenging than working on a jet fighter which had the world talking. The Arrow was about to make Canada a world power when it came to developing and manufacturing fighter jets.

“We were far ahead of everyone, especially the U.S.,” said Bill with great pride.

“It was the hermetic seals on our electrics and our hydraulics which set us apart. No other plane had what we had.”

The Arrow was developed to combat Soviet spy planes which were regularly invading air space over Alaska and Canada’s northwest.

The Arrow had a wingspan of 50 ft and was 77 ft in length. Its loaded weight was 68,605 lbs.

While there are a lot of other specs to go with those, the major feature of the jet was its speed – maximum Mach 1.98 (1,307 mph) – and its ceiling altitude was 53,000 ft.

The highest altitude passenger plane in use today, 60 years later, is the Gulfstream G650 which has a cruise ceiling of 51,000 ft.

Bill explained that the hermetic seals and hydraulics that had been developed were what allowed the Arrow magic to happen.

“We needed to have our electrics in hermetic seals to keep the air pressure consistent around them. When the plane was at altitude, we had to ensure everything would work,” he said.

During this part of his tenure, Bill said his team had a lot of meeting with U.S. representatives who were seeking to understand how the Canadians were doing what they were doing.

“We had a lot of meetings with U.S. officials. Each time they came around, my boss would say run off of a copy of that design and give it to them. That bothered me,” recalled Bill.

“Why would we give them our technology. I asked a couple of times, ‘Are you sure you want to give that to them?’ I was told, ‘Why not? They are our ally’.”

The key to that situation, said Bill, was the U.S. was not interested and never would be interested in buying fighter planes from any other country. If it was not U.S. made, they were not interested.

“The U.S. wanted our plans and theory, not our jets. I didn’t like giving away our work for free,” said Bill.

Despite the advances in technology which made the Arrow the fastest jet at that time, there were issues.

It was not until some research was assessed from firing eight test models out over Lake Ontario did designers realize that the “steady plane” of the wing’s front edge was “no good”.

“The break in the front edge of the wing solved the in-flight problem,” said Bill.

“The tests really did it.”

And with that, the Arrow was on the edge of making history.

But….

With the U.S. feted with all the information it needed, and England an interested customer, but one which did not have enough financial resources to be a serious bidder, the days of the Arrow came to a screeching halt with an edict from then Prime Minister John Diefenbaker to kill the project.

In keeping with much of the lore of the ill-fated Avro Arrow, its, although sad as far as Canadian history goes, somehow fits its meteoric rise to infamy.

“The day it was cancelled was like any other day. I was sitting at my desk and an announcement came on, “As of now, the Avro Arrow has been cancelled. You are all fired. The security people will see you out of the building,” recalled Bill.

“It was horrifying: thousands out of work just like that.”

Bill was one of the lucky ones. He got two more years of work, shifting over to the CF-100, but most were not so lucky.

“Most of the people I know went to the U.S. to work,” he said.

The end was brutal. Everything was ordered destroyed.

“They came in and cut up the actual jets right in the hangar with blow torches: brand new planes. It didn’t make an ounce of sense. All the investment was done. It was ready,” said Bill.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

But with the Avro Arrow it seems very much to be a living history as there are several conspiracy theories about what would lead Diefenbaker to not only scuttle the project, but to wipe it from the face of the earth, especially given its stature as a source of national pride.

As much as the lack of a customer to buy the jets was part of the mix, Bill says there were other complicating factors.

“The fact we gave the U.S. drawing after drawing, they didn’t have to buy anything. The Canadian Air Force wanted it, but the government didn’t want to pay for it,” he said.

“And aside from that, two of the key people involved just didn’t get along. Our manager at Avro and key government representative had what you would call a personality clash. They just didn’t like each other.”