(To view our March/April 2019 issue of ClubWEST online, click here.)

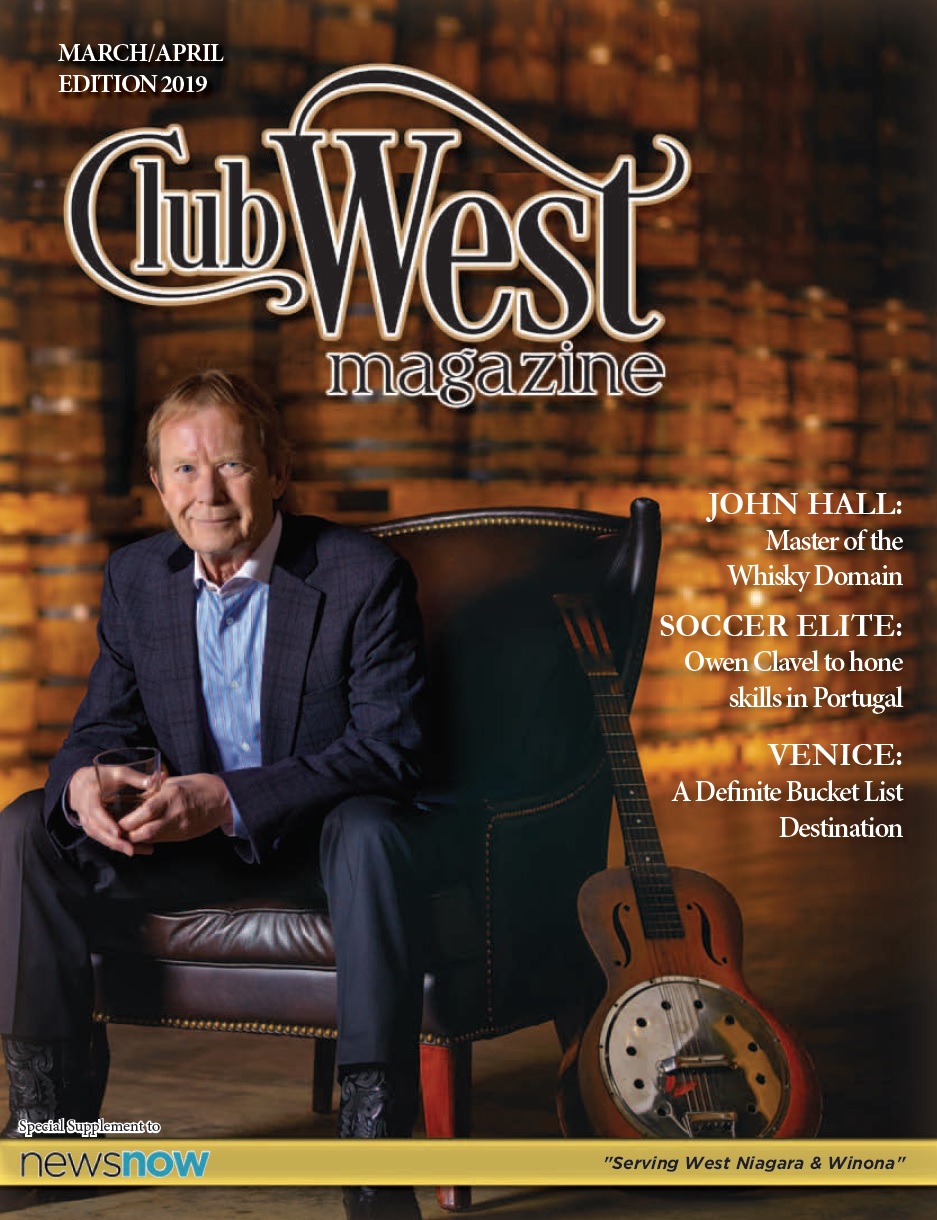

John Hall’s passion changed an industry, a company and lives

By Mike Williscraft

It is rare in this age of global economy that one person can move the needle in an entire sector.

It is even more rare that one person could reset and refocus an entire industry while setting it on a brand new track to world prominence.

Grimsby’s John Hall is that rare individual.

As a youth growing up in Windsor, Hall knew from an early age what he wanted to do with his life.

“I grew up in Windsor and always wanted to be a whisky maker. Hiram Walker (Distillery) was in Windsor. They never wanted to hire me as a whisky maker, which turned out to be a good thing,” said Hall with a laugh.

As with many things in business and in life, timing is everything, but when Hall decided to invest in Reider Distillery in 1992 there was nothing to indicate anything positive in the company or the whisky industry – just the opposite, in fact.

As described by Hall in a 2009 interview for Grown in the Garden of Canada:

The History of the Fruit industry in Grimsby:

“The facility here originally was strictly a distillery that had started back in the mid-70s. A fellow by the name of Otto Reider, who actually immigrated from Switzerland, was the owner. When he came to the Niagara area, he discovered all of the glorious fruit that grew in the area, the cherries, the strawberries, the plums, and the grapes and decided that this would be a great place to build a distillery and make eaux de vie’s (a.k.a. Schnapps), eaux de vie’s being distilled alcohol that is made from fruit. Eaux de vie’s are very popular in Europe, but not so popular in North America. So Otto Reider actually made some excellent, excellent eaux de vie’s out of Ontario grown fruit but his only problem was the marketing of it. Because people in Canada drank whisky and vodka and rum but they didn’t drink eaux de vie’s such as Kirsh and Slivovice and Poire Williams, he had limited success and unfortunately the company was ailing. In 1992, I came across it and discovered that it would make an excellent winery as well as a distillery, so I invested in it and changed the name to Kittling Ridge.”

Now, one may think from that start the rest was history, but the fact is, the work had not even begun.

When Hall acquired Reider, it came with another “acquisition”.

“John likes to joke that I came with the building,” says Bill Ashburn, who started at Reider after studying chemical engineering at Niagara College and gaining some wine industry experience at Jordan & Ste. Michelle’s Cellars.

While expanding the whisky distilling aspect of the business was central to his long-term plans, Hall knew the business plan had to be better rounded.

“He started the winery, Kittling Ridge, with the premise it would provide the cash flow to allow us to create whiskies which take many years to mature,” Ashburn recalled, noting Hall brought an extra ingredient to what would prove a phenomenally successful recipe.

“What John brought was passion and he tends to bring passion out in all those who work with him. He could get you to do things you never thought possible. He never has a down day. He just takes things as they come and keeps moving along,” said Ashburn.

“Other distilleries like Potters in St. Catharines and Corbyville in Corby were closing. Everyone thought, including me, those closures were the death knell for the industry. John thought differently and he did something about it.”

Indeed, history shows, 1992 was the low point in Canada’s whisky distilling industry.

“Canada had peaked in the whisky business in 1982 with eight million cases sold. In 1992, that had declined by half. They had lost sales of four million cases,” noted Hall.

“Distilleries were closing left and right. There were seven distilleries left in Canada. Today, there are nearly 200 with about 120 of them doing whisky. I raised the bar on Canadian whisky. I was just starting my business when the industry was at its lowest, but Forty Creek was the third largest distillery of premium deluxe whiskies within 18 years.”

To Hall, the core reason for this was quite simple – the industry had not attempted to reinvent itself for more than half a century.

“I intended to bring excitement and innovation to the whisky category. It was dull and boring. There was nothing going on. There was nothing new. I wanted to shake things up and regenerate it,” said Hall.

“1939 was the last time anything new was introduced. That was Crown Royal.”

With the bones of his plan starting to set, developing a solid infrastructure of staff and marketing were other steps in the process.

“From 1992-99 were the formative years. With the winery creating the cash flow, we were able to lay down some great whisky stocks,” said Ashburn, who remains Forty Creek’s master blender

“What a lot of people don’t know is that from 92-99 we were selling a lot of whisky to Taiwan through part of the business called Canadian Company, which preceded John. It already existed, but he took it internationally.”

With early stocks maturing while the business continued to grow and evolve, Forty Creek’s staff was getting things done, while Hall took to the road in a literal door-to-door effort to drive sales.

“Product development has always been my passion. John gave me the opportunity to be inventive in all aspects of product development in this company,” said Ashburn.

“John was on the road far more than he was here. He put great trust in his staff. When he was out on the road, he trusted things would keep moving at home.”

Hall’s tales from the road are as legendary as his accomplishments. Sitting with major liquor store retailers in Florida, stopping in at countless bars and giving free taste tests in New Orleans was part of his routine for many years.

The hours and work were relentless, but with purpose, says Davin de Kergommeaux, author of the award winning book, Canadian Whisky: The New Portable Expert and founder of the Canadian Whisky Awards.

“He went around making sure people got to know Forty Creek and Canadian Whisky. He did something that no other distiller had done. He started up his Program to promote his whisky, with a very very long vision, he wasn’t looking for immediate pay off,” said de Kergommeaux.

Part of the groundwork was a lot of miles, driving and walking.

“He did things like walking up and down Bourbon Street pouring his whisky for the bartenders so they would know who was behind the label. Now, if you go up and down Bourbon Street, Forty Creek is in every bar because took he time to talk to all those people. He did the same thing in other places in Texas, for example, where he would find out where bartenders hung out after work and he would pour for them.”

“He treated everyone with the same welcome and respect. John also invited people to visit his distillery when no others were doing this. He set up the shop and he did tours so people could actually see what was going on. People started to take ownership and what has happened over the years is that this group of people, and it is a huge group, is almost like a Forty Creek cult. There is great loyalty there.”

But all the customer service and groundwork would not have mattered had the quality not been in the bottle to back up what Hall was selling.

“John came into the Canadian whisky industry at a time when distilleries were closing, and Canadian whisky didn’t have a very good reputation. People had made very unfair assumptions about Canadian whisky. John wanted to stick up for himself,” said de Kergommeaux.

To nail down that part of his overall plan, Hall showed great patience.

“First of all, he did not release his whisky until he was really sure that it was a good representation of him and his distillery. So when he started distilling, I can remember when – maybe 20-plus years ago – it was about 10 years before he released his first whisky.

“His strategy was that he would have whisky at the same price point as others but his would always be a little bit bigger and a little bit more flavourful. He succeeded in that. Then he set out to connect with

other distillers, drinkers and influencers,” said de Kergommeaux.

“He started doing the special releases every year, and nobody was doing that, nobody at all. These special releases have really have become quite sought after. The very first one was called Small Batch. I’ve seen some of the small batch go on the market for $2,500 a bottle.”

But, again, the thinking behind the growth plan was intensely strategic, well thought out and timed perfectly, de Kergommeaux added.

“John addressed the American market very intelligently. Other people were shipping down mixing whisky to sell at $14 a bottle or less. John really

went after the drinkers. I remember I was talking to him at one time and John said he worked about 200 days that year showing and pouring whisky for people.”

And the years of effort rooted Forty Creek on a steady path of growth and success. That success not only transformed the business but placed Canadian whisky on the world stage.

“We were seeing consistent double-digit growth. From 2009 to 2014, the whisky industry only saw three per cent growth but Forty Creek had 65 per cent growth. We were responsible for 34 per cent of all the industry growth over a five-year period,” said Hall.

“I had always hoped for success but I never thought there would be a day when I was dancing with the giants of the whisky business.”

Among the giants with which Hall was dancing was the Campari Group, the world’s sixth largest distilling company.

Appleton Rum, Wild Turkey, Grand Marnier and Sky Vodka are all included in Campari’s stable of products.

After 22 years of growing Kittling Ridge Winery and Forty Creek Distillery from nothing, Hall knew he had done all he could with the company.

“Campari had the machinery and infrastructure to take Forty Creek further – especially in the U.S and Western Canada – with more distribution and more sales people on the road,” said Hall, noting there were several suitors for the business.

While Campari had the internal resources to grow the Forty Creek brand, it also had a much larger marketing budget.

“I never used TV. I used radio, billboards and magazines mainly, but it’s great to see Forty Creek on TV,” noted Hall of the commercials now seen regularly during prime time and major sporting events, which highlights the company’s roots in Grimsby.

“It shows the support for the brand and where it comes from.”

After selling Forty Creek in 2016, Hall stayed on for two years in an advisory capacity and acted as the company’s chairman of the board.

Now, he is enjoying life with his wife, Eileen, his adult children and, as of this past November, five grandchildren.

“I like to go fishing and travel,” said Hall, followed by an extended pause. “The travel is a lot different than it used to be.”

And when he does travel now, he does so as the first inductee into the Canadian Whisky Hall of Fame. This recognition was bestowed upon a surprised Hall last month as part of the Canadian Whisky Awards in Victoria. B.C.

“There is not a checklist of boxes for the hall of fame. The hall is for the people who have made a significant contribution to Canadian whisky,” said de Kergommeaux.

“Somebody like Samuel Bronfman, if he were still alive, or people like that who have really moved the category forward I would think would also be candidates. I think John Hall is the only person today who really qualifies. He is the first inductee and we will add more people as they make their contribution.”

For Ashburn, he was elated to hear the news of Hall’s induction.

“It’s fantastic,” said Ashburn.

“Forty Creek had six of us there to support John. We wanted to be there for him. We wanted to spend some time with him in Vancouver, but no way. The number of small distillers who wanted to get a minute with him, get some advice, we could not get near him.”

And that kind of positive interaction with people, whether industry colleagues or customers in the South Service Road retail shop, is part of what sets Hall apart, Ashburn added.

“Twenty two years I worked with the man, not for, with. It was never a boss/employee relationship. It was a highly collaborative effort and he made me and everyone in the company feel that way,” said Ashburn.

For Hall, he took the honour as he takes most accolades, with his “aw shucks” attitude.

“I was surprised. Davin had just asked me to be the keynote speaker at the 9th annual awards night as far as I knew,” said Hall.

“I was just giving some encouragement and advice to those starting up because it is not easy. It is 24/7. I think it went over pretty well because I was swarmed afterwards. I think the hall of fame induction was quite remarkable.”

Now that Hall’s transition time with Forty Creek is complete, he said he has kicked the tires on a couple of potential business ventures but nothing has clicked.

“It’s nice now, but it took a while to settle down. You don’t go from 100 mph, day-in, day-out and then just stop. It took me a while to slow down. I am enjoying my time now,” said Hall, adding he has a couple of pastimes to keep him busy.

“I like fishing and I have always loved all kinds of music. In the mid-60s I played saxophone in a local band. Today, while very rusty I do get pleasure from playing my saxophone, guitar and ukulele.”